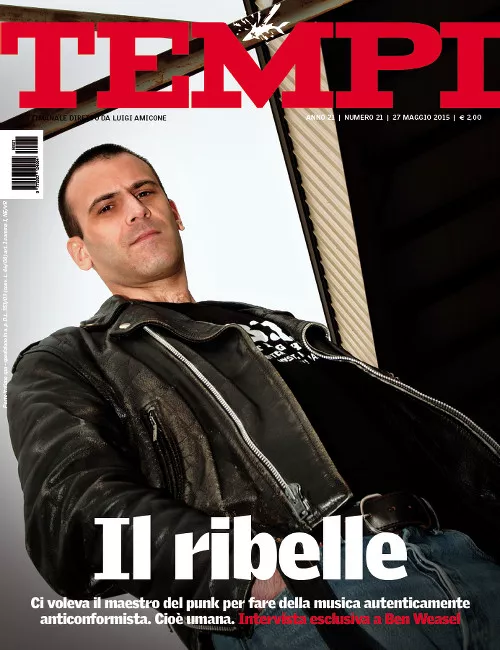

Exclusive Interview with Ben Weasel on “Baby Fat”, Punk Rock and the Human Condition

In the firmament of music, Ben Weasel is not exactly dying for a bit of fame. He’s almost proud of not having zillions of fans. But the ones he has – who are enough to allow him to make a living – go literally crazy for him. Considered the father of American punk rock, he’s one of the holy trinity of the genre, along with the Ramones and the Queers. His historic band, Screeching Weasel, was founded in 1986 (and – by the book – broke up and reformed several times). In some way or other, it inspired almost all punk rock bands in the US, including some that have outdone it, like Green Day and Blink-182. Ben Weasel is a legend. Better: an idol. So last summer it didn’t take him long to raise the necessary funds from his followers to produce his new album, Baby Fat. Forty thousand dollars in a month. Crowdfunding.

They say that you either love or hate Ben Weasel. An inveterate punk, he just can’t join the mainstream. He’s never accommodating to anyone, not even recording companies, let alone his “colleagues”. In his albums, he has fun turning punk rebellion on punk conformity, managing to make enemies among his friends. Always at his own expense, of course. Some affectionately call him “everybody’s favorite asshole”. Born Benjamin Foster in 1968 in Prospect Heights, in the Chicago suburbs, and expelled from three schools in his youth, he has assiduously disturbed the public peace with his pen and his voice, and is now universally considered a guru in his field. No-one would disagree with that. Not even today when Ben Weasel has converted to Catholicism, is married with three kids, and lives near Madison, Wisconsin, where his main activity is child-care during the day. In 2013 he even wrote a Te Deum for Tempi, thanking the Eternal Father for having made undeserved gifts to the world, like St Catherine of Siena and “our persistent Church”.

The truth, probably, is that Ben Weasel is so utterly punk as to seem punk even to punks. When he does something, he does it in a radical way. He writes and plays not to “create noise” but because he strongly believes – as he explains in this exclusive interview for Tempi – that he must say something with his music, something that is not just anger, emotion, or a dramatic outburst. In his new album, not one single note is there by chance. Screeching Weasel may soon come on tour to Italy, the home to many of their fans. And for Ben, that might be the time to make a dream come true to go to La Scala in Milan and enjoy an opera. Because the guru of punk rock now also loves opera. In fact, Baby Fat, the new album, is a real opera, to all intents and purposes. A rock opera. The album will come out with its own libretto, complete with characters, a plot, scenes and récitatifs.

The dialogues and texts are brimming with cultural references. Shakespeare and the Psalms jostle with more popular genres, destined for the connoisseurs of Charlton Heston and West Side Story. In musical terms, the album is an equally rich mixture of rock genres. From authentic punk rhythms it moves to heavy metal, among motifs from Westerns à la Morricone, and choruses which would not look out of place in grand musicals like Les Misérables. Baby Fat has no anarchic-like tendencies to griping. No politics, nor ideological manifestos. Something a lot bigger is at stake.

The idea, Ben remembers, came to him four years ago, when he was riding a media storm over the infamous South by Southwest incident. The rocker who had stepped out of line had ended up in the meat-grinder, and almost no-one seemed to want to stand up for him. Even the band had dropped him. It really looked like the end. But instead, after a period of silence, Ben seems to have risen above it. Screeching Weasel reunited and began to play again, better than before. Even this ambitious project popped up. It’s madness, clearly. A rock opera in two acts. The first is released on 26th May. Here is where our interview begins.

Why a rock opera?

Kind of a long story. I’ll try to make it short. About four years ago I had this big blow-up on the Internet. I socked a couple of ladies – which you don’t do. However, there was all this stuff going on on the Internet, and I had real life to attend to as well. My wife was seven months pregnant with our son, this new baby was coming and we already had a couple of three year old twins running around as well. So we needed a bigger car, we bought it, and it came with a subscription to satellite radio. I never listen to music in the car, but I said: «Ok, I’ll try it out». I turned it on and I came across this opera station – a 24/7 opera station from The Met in New York. They were broadcasting Rigoletto, and I thought: «This is terrific». There was something about it that really moved me. So I dived into it and began to educate myself about that opera, I decided at that moment that I was going to write one and that it was probably going to be based on Rigoletto, because in that story there were parallels to what was happening in my life.

One particular idea struck me. In the first scene Rigoletto is really this loathsome toad of a person, he’s a horrible character. But then the scene ends and we see him in his home life, and he’s a very different man, his whole world revolves around his daughter. He’s not a good character, but he’s very human. His love for his daughter is almost obsessive and ultimately destructive, so you can see the ending coming a mile away. And like a lot of people, especially people who aren’t religious, he’s very superstitious, so when this man puts this curse on him, he really goes into a tailspin, and the curse becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I was drawn to the theme of the public life versus the private life. I thought it was a perfect scenario to be updated with rockstars and athletes and movie stars instead of dukes and kings. Another thing I wanted to explore was the idea of success: being famous and how that can be an isolating factor, turning you into a monster. This idea that if you get wealthy and powerful enough to gain everything you want, you can really find yourself in a living hell.

You said it’s about public life and private life, but Baby Fat is a lot about good and evil…

Oh yeah.

… and what is noteworthy is that though there are many references to the Catholic doctrine, there’s no moralism in it, no bigotry.

That’s all intentional. I mean, If I was to sit down and analyze this – which I maybe don’t like to do but I don’t want to be coy with you – in very rough terms, I would say the character of Swank represents evil, the kind of evil I spoke about before. And then good would be represented by the character of Poveretta, who is not all good. I made her a theologian to underline the idea that her faith is largely intellectual. It has never really been tested, and what happens in this story is that her faith becomes tested and she has to make a decision whether she is going to really put her money where her mouth is. And then the character of Baby Fat… He is to me just like Rigoletto, he is everybody, he is humanity, and kind of struggling. This love that he has for his daughter will end up to be her ruin, as it is in Rigoletto. Because it is a sort of love that is based on possessiveness, it doesn’t enable her to have freedom.

So should we expect no redemption for her in Act II?

In Act II there will be redemption. Baby Fat is her ruin in the sense of what he’s to trying to get for her. In Act I he is trying to protect her, and clearly that doesn’t work. In Act II what’s going to happen is, he is going to try to avenge her, and that is not going to work either. So she will have to make a decision. At the end of Act I she finds herself in this horrible situation that is rape, she is struggling with the idea of vengeance, she will have to decide if she has to turn away from God. In a prayer, she will ask Jesus to turn away. It’s a form of pride, really. Her need for vengeance is so strong that she thinks she can’t be helped, and she knows that this is evil.

Why are you trying to upset our common idea of pride?

Because I think that fifty years ago or a hundred years ago the sin of pride was understood a lot better than it is now. Now if we say pride we just think that somebody is arrogant. I think the real meaning is different. You can find it for example in The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene, in which, at the and of the novel, Scobie commits this ultimate sin of suicide because he just decides that God can’t save him. It’s sort of a self-pitying attitude. He wants to be saved, but God cannot save him.

That’s the kind of pride that I was interested in, the kind that causes a lot of people today to say, as they find out that you are religious: «Oh, I wish I could be religious too, I just can’t». The implication is: «I’m just too smart for religion, I wish I could just be an idiot like you, and believe in God, because it would be so comforting…». But it’s the exact opposite of the truth. Religion is not about comfort, actually it is supposed to make you very uncomfortable. Here’s why that kind of pride really intrigues me, and why I thought it was good for Poveretta to have that kind of crisis in Act II. It’s the theory versus the practice of her religious beliefs, which is underscored by her being a theology student, because she is naturally inclined to look at the intellectual part of the faith. The head more than the heart.

It’s strange that we had to wait for a punk rocker in order to see a piece of art giving some Catholic testimony. Don’t you think?

You know, if you look at the first half of the 20th century, there was this incredible group of Catholic artists, especially writers, and particularly in the West, and that’s all gone. The serious thing is taboo now in arts.

What do you mean by “the serious thing”?

The serious thing. You can go out there and write your dopy books about angels that will be massive best-sellers. Or maybe you can say: «Yeah, faith is ok, as long as we take away all the key thought of it and we criticize the institutions…». You can make this kind of pleasant living-in-the-clouds stuff, with angels and wings. But if you get into the real heart of it, that’s taboo. That’s really the last taboo, certainly in America and I think probably in Europe as well.

Nobody really knows where artistic inspiration comes from, what the genesis of art is, and I think that for most of modern history going back to the start of Christianity, it was presumed that it came from God. Now it’s a psychological matter. In the first half of the 20th century, a lot of the art that came out, especially in the Twenties and Thirties (from German Expressionism on), was concerned so much with the psychology of the individual. It all became about man struggling against himself and his own psyche. That led to this kind of obsession with self that we saw come about in the Sixties, with the idea that the individual, and especially the individual feelings, are supreme. That’s where we are now.

The same applies to the modern political arena, where you see the word “feel” come up a lot. We see people who want to restrict our First Amendment, our right to free speech, because certain things make people “feel” bad. This happens in the American left, that was traditionally the supporter of free speech; it was the right wing that wanted to censor everything, from pornography to films, to music… That’s completely flipped now. The people who want us to shut up are the people on the left.

This is not an American exclusive. But how does it relate to art?

I think we’ve lost that connection, that idea that – whether you believe in a Christian God or not – the artistic impulse is divinely inspired, therefore we only can look at ourselves. In punk there’s a lot of bad political music, because if you don’t believe in God and you don’t believe particularly in the concept of Christian hope, the hope of a future resurrection, not of being up in the clouds with angels but of a new Heaven on Earth, and a new life that involves creativity and action, and actually being and living in union with God, if you don’t believe in all these things, then the solution to the human condition has to come from within. For most people it has to be a political solution.

Certainly politics has its place, but politics and art are a really bad combination, it’s almost impossible to do it well. That’s not the job of the artist. When we make art, we can’t go out with the idea that we’re going to change the world, because we’re going to miss the whole point. Our point is to comment as sincerely as possible on the human condition. Whatever way we do that, our best would work to that end. If you don’t get that, then you’re going to create stuff that doesn’t have much lasting value.

Are you saying that one has to be Christian to make good music?

No, you don’t need religion, you don’t need to believe in God to make great art. But you need to understand the idea that there’s something not entirely of your own making, or at least something that you can’t understand, a creative impulse. I think there’s some common ground there, but we’re living in a culture right now that is stuffed with offense, with being offended and taking offense, and that’s very bad for art.

Why is it bad for art?

Well, there’s this idea that we shouldn’t have to feel bad, and that people, when they say something bad to you, they can hurt you. Of course people can say things that do hurt you, but the proper response to that is to not let that define you. The solution is not to shut other people up.

It’s a problem artistically, it’s a problem even politically, because there are so many things that we can’t say, and if we can’t discuss things, we’re never going to find out solutions. Take for example gay marriage. Now people decide that gays should not only be allowed to marry, but they should be protected on the federal level by the Constitution. The problem with that is a question that was never given a serious answer, but was in fact laughed at. The question was: if you do that for one group of people, how can you then exclude anybody else? But it has always been considered ridiculous, it was not even worth discussing. Well, it’s very interesting because now that the tide has turned, the answer is different. It is: «Who cares?».

There is something really dishonest going on there. And it is possible only because everybody is scared to look like a right wing religious nut, when it was exactly just a question of logic and law.

Do you think there will be similar reactions to your Baby Fat?

Do you think there will be similar reactions to your Baby Fat?

Yes. There are a lot of people who dismiss everything I say because I’m apparently a right wing Catholic. I’m not right wing, I don’t have a political ideology. Politics is important, but it’s not the solution to the problem of the human condition. And my job is to comment on human condition.

So, are people going to have a problem with Baby Fat? Yeah, absolutely. I can guarantee people will be offended because I dared to create a scenario in which a woman is raped. They are going to decide somehow that I approve of rape or that I blame Poveretta for that situation or something. Obviously it was a deliberate choice, because I’m paying homage to Rigoletto, and also because it’s an incredibly emotionally charged situation, a devastating violation of an individual, of their liberty, of their sexuality… but from my perspective that scene has very little to do with rape.

I had a guy in my band in the early Nineties who saw the Quentin Tarantino film Pulp Fiction, and he was carrying on a conversation with me in which he argued – and he really seemed to believe this – that Tarantino used the word “nigger” in the film over and over again, because he just likes using the word “nigger” and he wants to be able to use it without being criticized. I thought: «That is insane! You don’t understand art at all!». But we really have come to this point.

I really believe this is what happens when you remove religion from society. Society gravitates towards it anyway, just unconsciously. So we don’t have organized religion anymore, but we created our own religion and now we are really like the 17th century Puritans. We want to publicly shame people, we want to put a scarlet letter on their chest. Is that good for art? Is that good for society? No, it’s not good for anything.

If you ever mention race, or sex, or homosexuality, you will be branded a homophobe, a sexist and a racist, even though none of those issues will ever enter the conversation.

You’re telling Tempi, the «homophobic, sexist s*it»!

It is particularly obnoxious to me for a couple of reasons. One, I have family members and friends who are gay, I love them and I don’t consider them to be less than anybody else. Two, it offends me because it doesn’t have anything to do with the conversation, it’s just an attempt to shut me up. And the practice of shutting people up by this kind of accusation is very bad for art, it’s causing a lot of self-censorship.

Getting back to your question, I can almost predict that the rape scene is going to cause trouble, but this is not the reason why I did it. It’s not really about sex or rape, it’s about mending humanity. And the really important part is how the character responds to it. I’m not making a social comment on rape by writing about it. I’m trying to talk about something a lot bigger.

Do you think that you have reached your goal with Baby Fat? Do you think it touches “the serious thing”, as you call it?

I have no idea. I’m too close to it. When a record comes out, my policy is that I don’t read reviews, including fan reviews, for six months, because I’m going to get defensive.

Are you satisfied?

Yeah, but I mean, it takes me about ten years to look back and go: «This record did what I wanted it to do». You know, there were limitations. I had to figure out how to write recitative for rock music, which it had never been done before, but on some of the songs I think I did a pretty good job. The singers, the musicians and the producer did a phenomenal job. The question to me is, can you listen to the album and get the sense of story? Do you feel musical themes recurring? Can you tell when a theme begins and when it ends because of what’s happening musically? If that’s happening, which I think it is, then I’m reasonably satisfied.

The album only contains music tracks. Will you ever take the whole opera on stage with dialogues and everything, as it appears in the libretto?

That’s above my pay grade. If somebody ever wanted to do that I would be thrilled, but it cost three years of my life just to write and record Act I, and I wouldn’t even know where to begin.

Why does Rigoletto intrigue you so much?

One of the great themes of Verdi, who I consider as the best opera composer in history, was the relationship between fathers and their adult children. We see it over and over in so many of his operas. You know, he had always wanted to do an opera version of King Lear, and he died before he could do it, but that would have been the ultimate expression of that, I think. We have to explore the things that fascinate us, and I’m really interested in a father’s relationship with his daughters, because I have two.

Has this changed your relationship with your children?

Maybe I am more aware of the dangers of being overprotective. I had a lot of worries as a new father before the kids were even born. I think it’s a specific thing of the father, especially with a daughter. I was absolutely exploring that in myself while doing Baby Fat.

I am in every one of the major characters in this story. I am elements of this evil awful guy, Tommy Swank, his tendency to wall himself off. I have that tendency that you see in Poveretta to intellectualize my faith and try to avoid situations that would force me to live it. I am also in the character of Baby Fat, in his desire to control everything and to separate his public image from the person he is privately, with the paranoia that that can create towards your loved ones, and the bad decisions that you can make because of that.

Why create so many characters? It’s quite a complex way to express oneself.

The popular thing to do in punk is to write confessional songs or autobiographical songs. This is prized over everything else, as the only way of being “real”, not artificial. What I discovered, instead, is that you can catch a larger truth through fiction. In a way, what you are doing becomes more authentic, more genuine, it cuts closer to the bone because fiction allows you to not get caught up in the minutia of your own subjective experience. You are able to tap into the universality of your situation, because you’re not thinking about yourself all the time. Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare… none of the great artists sat around trying to work out their psychological problems through their art. They were trying to say something about life.

Have you been inspired by any other real person, apart from yourself?

No, the inspiration for the characters came directly from Verdi and Piave and Victor Hugo. The original play on which Rigoletto was based was Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse. It was a huge failure and I don’t know why Verdi decided to set it to music. I’m glad he did because I think it’s probably the best opera in the repertoire.

I looked at some of the themes that Verdi looked at, and expanded on them. I might have stressed things a little bit differently, so Act II will probably have the same ultimate conclusion as Rigoletto, but it’s going to play out a little different, because I am still very interested in this relationship between fathers and their adult daughters. What we’re going to see in Act II – the one thing I can say – is that Sardonicus has an adult daughter too, so there will be another female lead character. But I don’t want to say anything.

Is it fair to make a parallel between Baby Fat and what happened to you after the situation in SXSW? Your story is a case of ruin and redemption too…

I couldn’t live a calm happy life if I looked at myself as this terrible victim, but what I could do was, I could play up that bad guy angle publicly, and that’s what I still do today. As of that moment, my entire public life became a piece of performance art, where I wail about the hypocrisy and blah blah blah. That doesn’t mean that I don’t feel that it’s true to some extent, because there is a lot of hypocrisy actually. There have been several instances of musicians in my genre attacking people in the crowd. A few weeks ago a guy kicked a woman and spit on her, because she threw a bottle at him, and he was basically cheered for doing that. You know, he knows the right crowd, he knows the right people, his politics are correct…

So, it makes sense if you’re comparing my situation to the character of Baby Fat. He is like an insult comedian in a way. He puts down the people around him, and I do that too, but I’m also doing performance art. In one sense, it’s a comment on everything around me in my public life, but it is also a comment on me, and it is not always flattering. This is the part that nobody seems to understand. People say: «He doesn’t know how it looks when he does this stuff». I do. I know exactly what it looks like. It’s on purpose.

That has enabled me to sleep great at night. I don’t have any anxiety, in my private life I am happier than I have ever been. Except that right after it happened I said to my wife: «Well, everybody says my career is over and I’m sure it is, how do you feel about that?». And she answered: «Just relieved. You’ve been miserable. Ever since you started going up and performing again, you’ve been so unhappy, you’ve been angry». She was right, I hated doing it. So we knew we were going to be poor, but it was fine because we were happy.

But that’s not what happened. Your career was not over.

Well, that’s the funny thing, it turned out my career wasn’t over, I ended up coming back, making more money, drawing bigger crowds and doing better than I’ve ever done. But I’m still behaving as though my career was over, so I’m able to go out now and really enjoy what I’m doing. And I don’t have that anger and resentment, because I completely cut ties with the politics of that scene. I behave like a man who has nothing to lose. To a certain extent, I put it in God’s hands…

One of my old drummers wrote this thing the other day about how much he hates it when religious people say that they put things in God’s hands. You’ve got to do it yourself, he wrote. That makes sense, I suppose you can always do something about your situation, but part of having a relationship with God is understanding that very little in your life is actually under your control.

The way you talk about your relationship with God is striking. Who is your main inspiration in that? Where does that education come from?

I don’t really know, I’m largely self-educated. I was baptized Catholic but I never received the sacraments, so when I joined the Church as an adult I had to go through the RCIA program [Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults]. But I think that there was never a point in my life where I was an atheist. I mean, I was an agnostic, I thought that there was some sort of god up there who didn’t care about me, but I never believed in a complete lack of God.

From a life in which I made almost every mistake a person can make, the theme that really came true to me was redemption. We’re drawn to the Christ story because of the redemption part of it. It’s a huge theme in the history of Western literature. I think there’s something inherent in that that we understand as people, and that’s why all our films and novels are so often redemptive stories. To my mind, that idea of suffering and dying to self and kind of rising again is a very fascinating subject.

When did you decide to become Catholic?

I joined the Church almost exactly ten years ago. I had been a Buddhist for several years, but I had begun to realize that some of the things that really attracted me to Buddhism were in fact Catholic aspects of it. I had always been attracted to Catholicism, because as I said I was baptized but not raised in the faith, and my sisters and I were some of the only kids on the block who went to public school. Most of our friends went to Catholic schools and they would have to go to Mass on the weekend. I found the whole thing fascinating. But my mother had left the Catholic Church and she had been going to a Baptist Church, so when I was ten or eleven she made us go there and join the youth activities. That probably turned me off religion for decades. I hated it, it was to me cheesy and silly. To my mind it just didn’t seem serious about God, it seemed like a “Disneyfied” version of what it should be, and I’m speaking from the perspective of a ten year old kid…

So when I decided to leave Buddhism, I seriously looked at Catholicism. And what struck my attention at the time was the Eucharist. Some churches of my area in particular were doing eucharistic adoration. You know, they put the Host on display and then people come and pray before it… I started reading about it and I learned that it was really a literal belief in the body and blood of Christ present in the Host. I thought: it’s nothing else but so outrageous, so defiant, it defies everything that we know scientifically, it defies all our culture obsessed with science – which means: whatever somebody says that this week we believe in. I mean, it’s a really serious thing. I decided that if I was going to join a church, I had to go to one that offered eucharistic adoration, a sign that they were serious about the faith. While the ones where they play acoustic guitars and sing the Our Father, those were not for me.

What has convinced you to change your life and join the Church?

I’m a little hesitant to talk about my transformative experience, because it almost sounds like something out of a movie, it doesn’t sound real… Before I made the decision to join the Church I said: I’m going to try to pray. I had no faith that this was going to do anything, but I was just going to give it a shot. You know, one of the reasons I could never reconcile with Buddhism is because ultimately it’s self-directed. Your redemption in Buddhism is entirely up to you, and you only achieve it through your own power. But I had been a lifelong disaster. I spent two years as a teenager in a sort of reform school because I couldn’t get along in society, I ended up in a punk rock band because I didn’t fit anywhere else. A classic outsider. Really a failure in so many ways, and I had recently been divorced… I had been trying for thirty years to fix myself by my own efforts, and it just didn’t work. So I said: I’ll try praying, it can’t hurt.

I started to say a prayer every night and just ask for help in a general sense. I didn’t even know if Jesus was real in any afterlife sense. But almost immediately my life started getting much better. I did nothing, I changed nothing, but my life started getting better, and my problems started receding. Considerably. Maybe it was all coincidence, I have no idea, I’m not confident to sit here and say that God entered my life at that moment and made it better. I mean, it is undeniable at this point, but all I know is, it hooked me and made me want to try out Church and receive the Eucharist.

Of course there were intellectual reasons why I came to faith, various things I read, particularly about the resurrection. But it was really more of a heart thing than a head thing. I just looked at my life compared to the hell it used to be… I began to see changes in my art, I began to see changes in my life. But above all I stopped feeling bad about myself, I found I could stop making decisions that I shouldn’t make. There was a huge backlash in my business life.

Did your conversion irritate anybody?

Well, nobody was really happy, although I wasn’t very loud about it. I had made a much bigger deal about my Buddhism, and everybody thought that was wonderful. «Oh the Buddhists are so nice, they are so liberal…». But when I joined the Catholic Church, it was like I had just kicked their cat or something. There were one or two people that were seriously worried about me, including my mother. Even to this day, Catholic in certain circles, especially in punk rock, is an insult, just like calling somebody an asshole.

In some sense there is a contradiction between being punk and being Catholic. People associate punk with anarchy, doing what you want, being the opposite of Poveretta.

That’s an old-fashioned view of punk. It might have been at the beginning, but very quickly it became a kind of second wave hippy movement, a radical left wing. So, yeah, there is no room for religion, but only because religion is seen as inherently hostile to left wing values. I have been hostile to that notion since the beginning of my career. Even when I had no faith at all I was writing songs that specifically addressed the attack on conventional ideas of religion in punk.

What songs?

On the first album [Screeching Weasel] there’s a song called What is Right? that specifically talks about what if God really exists. On the second album [Boogada Boogada Boogada!] there’s Holy Hardcore, a kind of silly song written from the perspective of a punk rocker who believes in God. It’s specifically designed to provoke anti-religious people. And then the third album [My Brain Hurts] features The Science of Myth, in which I wanted to take an actual look at what faith is.

You have difficult relationships even with your world.

I chose punk because I thought it was the only place where I could just do whatever I wanted and there were no cool kids groups or whatever. But very quickly I began to realize that I was totally wrong, it’s just like everything else. I began to rebel against that from the very beginning, and that has always caused problems to me. In fact I have no idea how I have a career at all… The reason people say that I’m right wing, even though I’m not, is because the predominant voice in punk is left wing, and I have to criticize it. If the predominant voice was right wing I would be doing the exact opposite. Not just for the sake of doing it, but because I’m against any sort of unthinking allegiance to anything. I took seriously what they say in the hippy movement and in the punk one too: to question everything. I question everything, including your insistence that I question everything.

Let’s go back to Baby Fat. How did you choose the actors? They are all punk rockers, right?

More or less, yes. You know, there were certain people I knew I wanted right away, others that I wanted and I couldn’t get… The one that really stands out for me is Blag Dahlia, who is the singer for the Dwarves. He is Baby Fat in the opera, and in real life he is a serious hardcore atheist, although he was raised Catholic. He is about the strongest atheist you can imagine. His record covers feature naked women, sometimes drenched in blood, he loves sex and drugs… And he’s very theatrical. I had never paid attention to his band until I realized that what they did was great theater, which was what I needed – somebody who understands the theatricality of rock music.

I know that the fans probably would have expected me to sing the main lead, and the logical choice would have been to have Blag singing the bad guy, Tommy Swank, this drug and sex-obsessed character, but I wanted to cast him against-type. And I wanted to play the bad guy, because playing the bad guy is fun.

There’s a huge mix of music genres in the opera. Do you think your fans will understand?

A lot of them no, but you know, many punk fans don’t really know much of anything that came before the Nineties, they don’t even know a lot about the great foundation of rock and roll, Chuck Berry etc. So, it depends on the individual, but I also think that to some extent you don’t need much of a musical background if I’m doing my job right. So I don’t want to blame anybody. Ultimately if somebody doesn’t pick up on very specific little things, it’s not a big deal, but if they miss the larger point, maybe I didn’t do my job as well as I should.

Do you think this huge work will be paid back, both in terms of money and satisfaction?

As for the latter, satisfaction, I hope so. But financially, we crowdfunded it. There’s no advance to recoup, so we’re going to see royalties almost from day one, which is really gratifying, but it’s not going to be much money – not enough to make a significant difference in my family life.

Baby Fat is one of those things that you do even if you know that they are probably going to fail – they might fail creatively, they’re certainly going to fail financially. But if I don’t do this, then what am I going to do?

There’s already a tour on schedule this summer, after the release of Act I in the U.S. (May 26th). Are you planning to do some shows in Europe as well? Maybe in Italy?

Yes, we’re still on for a couple of European shows. With any luck we will get to Milan. I hope so.

Is it true that you have lots of fans in Italy?

I guess so. I’ve never played there with the band, I’ve just been told over the years that we have a lot of fans in Italy. I don’t know why.

You never played in Italy?

Well, I played in Milan in 1995 with The Riverdales, we supported Green Day. But I’ve never done it with Screeching Weasel, because the logistics of going over to Europe are difficult at best. Looking after my kids and my responsibilities at home stop me from going on long tours. And moreover, in most of the European countries taxes are punitive. I mean, I’m all for everybody having health care, but you know, when you go up in some of these countries and they act like: «Oh, you Americans are so backwards with your health care», I say: «Yeah, but we don’t punish people for coming and working in our country in order to pay for that!».

Anyway, I hope we can get over there, because I really would like to spend a day or two in Milan. What I really want to do is get out and see an opera at La Scala. To see an opera there, that to me is like the ultimate.

One last question. What does «we belong to the angels» mean?

That’s just a tribute to an interesting piece of American history. When our President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated he didn’t die right away, he was on his death bed for a while, and his Secretary of War [Edwin Stanton], when he died, is supposed to have said: «Now he belongs to the ages». A legendary phrase that people still remember to this date. But recent scholarship has said: no, he didn’t say that. What he most likely said was: «Now he belongs to the angels».

Anyway, in the concept of that song [We Never Knew] those words take on a different meaning, because it’s about this unique, secret relationship that this woman, Poveretta, has with her father Baby Fat.

My father was adopted, and when my grandfather died, he asked him from his death bed: «Do you want to know about your parents?». And he said: «No, you are my father», because he was very loyal to his adoptive parents. Well, many years later, about six years ago, he started looking around. It took months, but he found out who his birth mother was: she was a woman that he had known as a child, because his parents owned an apartment building and they boarded her there for several years. He remembered her, he knew who she was, and he also found out he had a half sister. So now I have this new aunt with a family of her own living down there in Arkansas – a whole part of the family speaking with southern accents…

I just liked the idea of their bond. There was this bond between my father and his half sister right away. I was thinking about that when I put that phrase into the story, this idea they’ve been in this bond even though they didn’t even know each other. That’s a real thing and it creates this kind of unique relationship that wouldn’t have existed if they had been raised together as brother and sister, for instance.That line, «we belong to the angels now», is like Poveretta’s commenting on this bond. It has nothing to do with death, it has to do with being in this unique relationship with each other.

It would be a good idea to include all this information in the comments of the libretto. For your fans.

They can read about it in this interview.

A short Italian version of this article first appeared in the latest edition of Tempi magazine.

0 commenti

Non ci sono ancora commenti.

I commenti sono aperti solo per gli utenti registrati. Abbonati subito per commentare!